When a Black woman who did DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) work reached out to see if I was interested in hopping on a call with a group of white people who were forming a coalition to address racial diversity in the running industry . . . I wasn’t. The idea that white people who knew nothing about race and racial work would be leading a coalition on racial diversity made my eyes roll so far back in my head, I heard my grandmother telling me to be careful or they’d get stuck that way. And really, hadn’t I already given enough free labor?

But an Indigenous community leader had already agreed to join the call, and she posted on social media that she wished the running industry had something similar to the outdoor industry’s DEI effort. Okay, I thought, I will do this in support of her. So I said yes.

We met on Zoom. There were two white men and one white woman, all in the running retail business, plus the Indigenous leader, the Black woman who’d brought us on and who was serving as their adviser, and me.

The call began with one of the men explaining that they’d all been deeply affected by Ahmaud’s murder. Ahmaud was a runner, and he had opened their eyes to racial violence and what it means to run as a Black person. They decided it was time to explore what the industry should do. The man’s eyes welled with tears. Here we go, I thought. Was I going to have to comfort a white man newly awakened to racial harm? I bit my lip.

The group went around in a circle introducing themselves. When it was my turn, I started by saying that the running industry is part of the problem. It is rooted in whiteness and white supremacy and this was what the industry needed to address.

The white people shifted in their chairs, and their faces went stony save for one man, who blew up.

“Don’t call me a white supremacist!” he said, his hands flying up in the air. “White supremacists are skinheads who hate people. KKK. Nazis. I’m not like that.”

I’d been on multiple calls with racially ignorant white people, but this was the first time white fragility had exploded in front of me. I took a breath and explained as I had for the podcast host that the definition of white supremacy was broader than the extremist understanding. I also told him that it was his responsibility to understand these terms if he was going to be involved in this work. He couldn’t hear me. He was too deep into defending his “good person” – i.e., non-racist – status.

“I am nice to Black people,” he said, defiant. “I put a kid in Africa through college. One of my best friends is Black. He, he, he named his son after me.” A common tactic, the “I have a Black friend” defense. I believe he actually repeated it. “I mean, my GOD, He. Named. His. Son. After. Me.”

I didn’t know whether I wanted to laugh or scream. The average Black person without a formal education knows more about racial issues in our country than a formally educated white person. White ignorance is part of what keeps a white supremacist system in place. If we don’t acknowledge it exists, then there’s nothing to address. White supremacy is the system that allows racism to flourish, and prevents racial diversity from being welcomed and celebrated. I often think of this quote from the hip-hop artist Guante: “White supremacy is not a shark, it is the water.”

It was clear to me this group needed to do a lot of reading and personal reckoning with their whiteness before we could move ahead, and so I said as much. After we hung up, I texted the Indigenous runner: What was that? She replied, What a meeting.

Often on calls, the people of color shared our experiences with racism. We talked about a lifetime of microaggressions, of feeling dismissed and not being acknowledged. Of our children coming home from a walk with friends and telling us that a white man threatened to call the police if they didn’t leave the neighborhood. We expressed how difficult it is for Black people and people of color to feel safe in running groups, in public space,

in these meetings. We talked about the stress of being the only person of color at an event. We expressed the reality of racial trauma, the real emotional distress and weight of being a person of color in the United States.

One person at a major running shoe brand disclosed that they were overlooked for a promotion because they didn’t have the “right look” for the job. Someone shared that a person they’d recommended was not hired because, as the manager put it, they had dreads. Another person at a different running shoe brand shared that they’d been dismissed in meetings and marginalized by colleagues. Not once, but on many occasions. “No, no, that can’t be true,” the white woman said. The person of color nodded that it was. The white woman was shocked: this happens in our industry.

Over time, the white people came to see how very different our experiences were from theirs. They began to understand that we came to this work weary and exhausted. That we live with the worry and the weight every day while they can step away from race whenever they want to, rest, take a break. We cannot. We are tired of explaining race to white people. We are tired of trying to get them to see beyond whiteness and white comfort to see us. We have little patience for their racial awakening, their processing, their trouble with language. Our lives are at stake. Our children’s lives are at stake. Get up to speed and get on board.

---

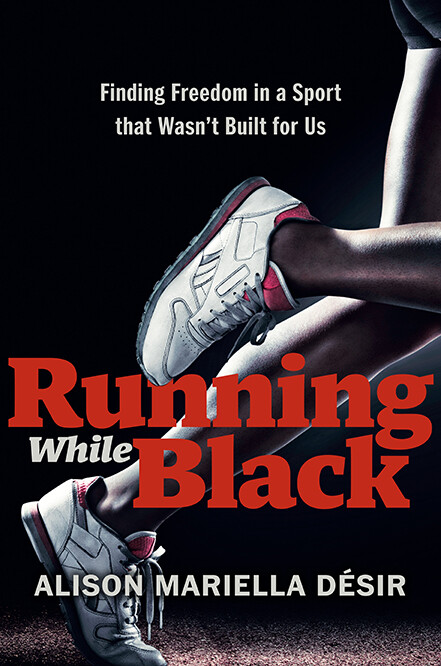

Alison Mariella Désir is an endurance athlete, activist and mental health advocate. Running saved Alison Mariella Désir’s life. At rock bottom and searching for meaning and structure, Désir started marathon training, finding that it vastly improved both her physical and mental health. Yet as she became involved in the community and learned its history, she realized that the sport was largely built with white people in mind.

To help make running more inclusive and welcoming to people of color, Désir founded Harlem Run, a New York City-based running movement, and Run 4 All Women, which has raised over $150,000 for Planned Parenthood and $270,000 for Black Voters Matter.

Désir is currently co-chair of the Running Industry Diversity Coalition, a Run Happy Advocate for Brooks Running and an Athlete Advisor for Oiselle.

A graduate of Columbia University for her Bachelor’s and two Master’s degrees, including a Master’s of Education in counseling psychology, Alison has been published in Outside Magazine, contributed the foreword for “Running is My Therapy” by Scott Douglas, and founded the Meaning Thru Movement Tour, a speaking series featuring mental health experts and fitness professionals.

“Running While Black” is her first book. Alison Mariella Désir currently lives with her son, Kouri Henri, and partner, Amir Muhammad Figueroa, outside of Seattle.

To learn more: alisonmdesir.com

.jpg.medium.800x800.jpg)